For this blog we are reprinting the story of The Great Rebellion which took place at Rugby School in November 1797. This version was published in The Laurentian February 1898.

“We passed last term the centenary of the Great Rebellion in Rugby School, which took place in November, 1797, in the Headmastership of Dr. Ingles. There had been another Rebellion eleven years before, but of this earlier one we have no particulars. All we know about it is that one boy declared it was “awful.” The origin of the Rebellion of 1797 was as follows: One day, as the Headmaster was walking down [to] the town, he heard the reports of several pistol-shots. These came from the spot where Loverock’s shop now stands, which was then occupied by one of the boarding-houses. On entering the yard of the house, the Headmaster saw a boy firing cork bullets at the study windows. He asked the boy where he had bought the gunpowder, and the boy confessed to having got it at a certain shop. The owner of the shop, however, denied the charge, and shewed from his account book that the supposed gunpowder had been entered as tea. This evidence seems to have satisfied the School authorities, and the boy received corporal punishment for telling lies. But the rest of the School were not satisfied with the justice of the punishment, so they turned out into the town, and, by way of retaliation, broke the shop-windows of the grocer who had caused the boy to be flogged. Upon this Dr. Ingles ordered the Vth and Vlth Forms to pay the expenses caused by the breakage of the windows—though no explanation is given as to why the Vth and Vlth Forms were singled out to defray an expense which the whole School had caused. At any rate they refused to do so, and at fourth lesson on a certain Friday the door of the Headmaster’s school was blown in by a bomb. But the whole School apparently did not break out into open rebellion until after second lesson on the following day, when the School bell was rung in an unusual and extraordinary way as a sign to the inhabitants of Rugby that a revolution had broken out. The Headmaster, perhaps foreseeing something of the sort, had taken the precaution of having his front door guarded by a soldier with a fixed bayonet. One boy happened to have seen this soldier, and he immediately reported it to the mutineers. Fags* were then sent to all the houses, ordering everybody to come at once to the School buildings. The mutineers then proceeded to nail up a certain passage leading from the School House to the Headmaster’s school, and to carry out all the forms, desks, and books they could lay their hands on, into the Quad, where they lit a large bonfire.

Dr. Ingles immediately sent messages to summon all the Masters. Strangely enough, however, they were not to be found, two of them having gone off to fish, and another to shoot rabbits at Brinklow.

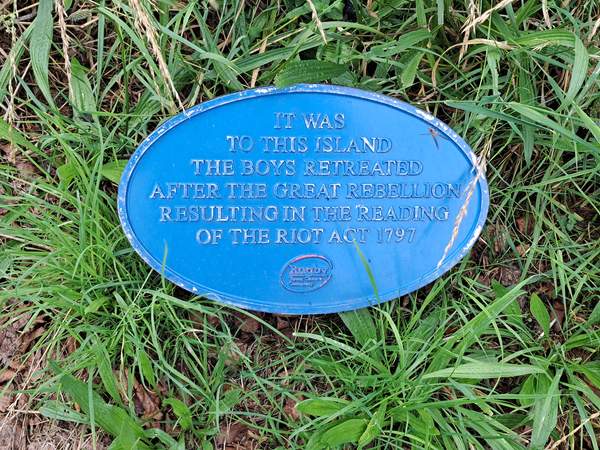

All this time Dr. Ingles had not dared to leave his study, and had it not been for the promptness of Mr. Butlin, the banker, who asked help from the dealers of a horse fair which was then going on in Rugby, the mutineers might have done far more damage. As it was, Mr. Butlin, at the head of a force consisting of a party of recruiting soldiers and numerous horse dealers, armed with whips stormed the position of the mutineers and forced them to retreat across the Close, and take up a position on the Island. At this time the Island was surrounded by a moat from 20 to 30 feet wide and several feet deep. There was a drawbridge over it at the point where the cricket pavilion now stands, which was raised by the mutineers from the Island, so that they now felt quite secure. Mr. Butlin then marched up to the moat and read the Riot Act, exhibiting his constable’s staff, while the mutineers watched him and jeered. Meanwhile, the recruiting party, by a clever piece of strategy, waded through the moat at the back of the Island, and took the fortress in the rear. The Mutineers surrendered without a blow, and were ignominiously led back by their captors. Then at last Dr. Ingles summoned up enough courage to leave his study, and spent the rest of the day in administering a richly deserved punishment to those of the Mutineers who were not expelled on the spot."

For other versions of The Great Rebellion see:

- A History of Rugby School by W H D Rouse

- Rugby by M H Bloxam

- from Elizabeth to Elizabeth edited by Robin Fletcher

* Fag/Fags was a term used in the nineteenth century meaning a junior man providing trivial domestic services to a VIth (shoe cleaning or fugging, message running, fugging corps badges, fugging out a study, toasting bread, etc).